Soon Santa Barbara saw an explosion in the export of agricultural products, wool and hides, fish, abalone and abalone shells. A similar expansion was taking place in imports, especially of wood and manufactured products. Most important, long term was an expansion in the number of people flocking to Santa Barbara. The population explosion would change the area forever.

One problem, common to all piers, was occasional damage from storms. On November 16, 1877, the local newspaper reported the “fierce winds at Santa Barbara injuring the wharfs.” It was only a prelude to the larger and more devastating storms that would strike two months later. On January 14, 1878 new reports said “high winds and heavy seas are breaking up the old wharf at Santa Barbara (the Chapala Street Pier) and carrying a part through the new wharf (Stearns’ Wharf).” On January 23, new accounts reported “there is a break in Stearns Wharf and waves have carried off 900 feet of the wharf.” The January sou’easter, together with assorted flotsam (mainly debris from the Chapella Wharf) had smashed out over 900 feet from the middle of the wharf. However, the pier was rebuilt by July of that summer (after Stearns forced the county to rescind a wharf license fee).

Then, on December 31 a new storm, together with a waterspout, pounded ships against the wharf once again and ripped out a new 100-foot section. Repairs waited until the following spring but once again they were completed.

Another challenge, one that would prove as dangerous as the winter storms, was the arrival of the Southern Pacific Railroad on August 19, 1887. “Ring the Bell!,” cried out the Weekly Independent, “Patience has its perfect work! After years of waiting, Santa Barbara’s millennium has arrived. Come all ye who are weary of stagecoach and saddle and ride at the rate of thirty miles an hour—so saith the Southern Pacific.” Although the initial line only ran ten miles up the coast to Elwood, it did connect southern California with Santa Barbara and the wharf saw an almost immediate drop in business.

Stearns responded to the competition by joining it. He built a new, 1,450-foot-long, wye or Y-shaped wharf in 1888. It jutted out from between Anacapa and Santa Barbara Streets and joined to his first wharf. The new wharf included a railroad spur that connected to his lumberyard and the nearby Southern Pacific Depot. Now the railroad could run right out to the wharf (and the original wharf was widened and strengthened); Stearns Wharf continued to be a success. By 1889 the local paper reported that the city could boost of the largest wharf on the Pacific between Sitka, Alaska and Cape Horn. However, the Y-shape seemed to weaken the wye-wharf and high seas destroyed it in 1898. It was never rebuilt.

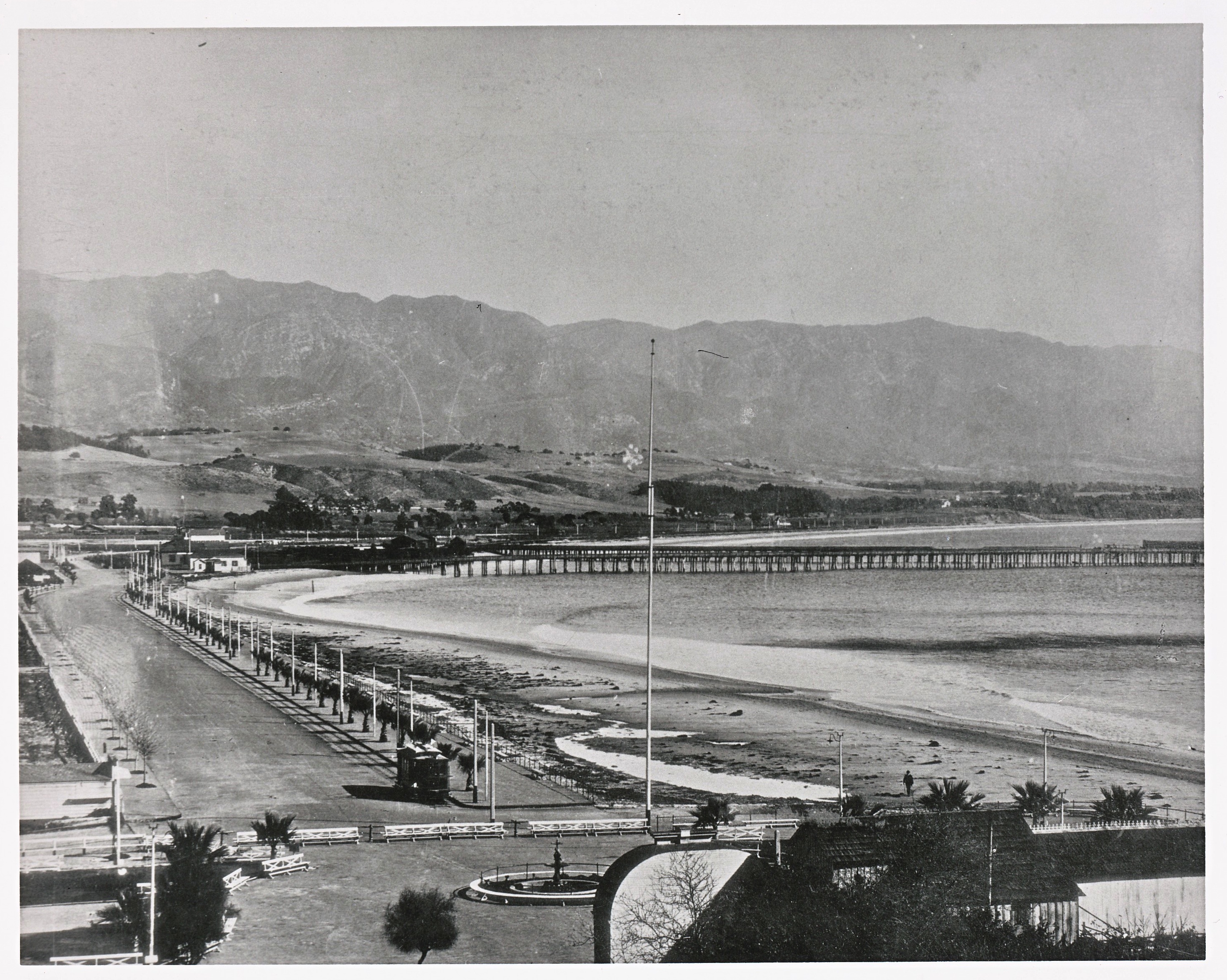

Picture (Stearns Wharf, Circa 1920)

But technology and life in California was changing. By the early 1900s there were faster and cheaper methods for moving passengers and cargo although freight handling for some high-bulk, low-value products (like lemons), remained relatively high until the 1920s. And though the vessels of the Pacific Coast Steamship Company had visited the wharf since the 1870s, they discontinued their stops in 1916.

At the same time, the wharf was becoming an increasingly important resource for recreation, used by local anglers and tourists alike and the mid-’20s saw the fishing barge Jane L. Stanford based at the pier.

However, the decrease in commercial business meant less money for repairs and a slow but steady deterioration of the wharf. Equally devastating was a fire that engulfed parts of the wharf in 1921. Embers, blown offshore from the nearby Potter Hotel fire (assisted by fifty-mile-per-hour Santana winds), started the fire. Because of the fire damage, and additional though minor damage from the 1925 earthquake, a group headed by Major Max Fleischmann rebuilt much of the wharf in 1928.

Worlds Record

Santa Barbara fishermen are claiming the record for the Pacific coast in the number of jewfish caught off one barge during the last three months. Captain Bill Hall of the fishing barge “Jane L. Stanford” said that 43 jewfish have been taken off the Santa Barge in 90 days. The Santa Monica barge is second with a total of twenty jewfish during the same time. Six jewfish were taken on the barge last week. Mrs. Hall hooked a 322 pound fish while her husband was landing a 78 pounder.

—Oxnard Daily Courier, February 13, 1928

During the ‘30s the wharf saw a mixed use, although it maintained its mainly commercial nature. Although some of the commercial fishing boats now called the recently completed (1929) Santa Barbara Harbor their home, most still had to bring their catch to the wharf for sale. The S. Larco Fishing Company, Santa Barbara’s dominant fish retailer and distributor, remained on the wharf into the ‘40s.

In 1941 the Harbor Restaurant was built on the wharf and it quickly became one of the main attractions and moneymakers for the wharf (and in some ways ended the reliance on shipping, transportation). But Pearl Harbor and World War II were on the way, and in the spring of 1942 the Coast Guard took over control of the wharf and restricted public access. That stayed in effect until 1944 when the wharf, under new owners, was reopened to the public.

Soon after, in 1945, actor James Cagney and his brothers bought the run-down wharf for $200,000 with hopes of turning it into a major tourist destination. That dream ended when the “City Fathers” expressed opposition to the idea of a wharf amusement park. Cagney’s group sold the pier just three years later to Leo Sanders (after filming Fort Royal on the wharf).

Unfortunately, Sanders rarely had the money to properly maintain the wharf. It continued to deteriorate until 1955 when Sanders sold it to George V. Castagnola, owner of the area’s largest local seafood company, and Norman Hagen, owner of a sportfishing fleet in Newport Beach (who had been given permission by Santa Barbara to open a sportfishing operation on the wharf). Their Santa Barbara Wharf Company soon began to replace more than 1,900 piles at a cost of $208,500. From 1955 to 1972 they spent over $1 million on repairs and improvements. Among the improvements were the renovation of the Harbor Restaurant and the importation of an old gasoline station onto the wharf—which was soon converted into Moby Dick’s Coffee Shop.

From the 1940s to the 1950s the fishing industry had provided much of the commercial revenue to the wharf. Most of this was commercial fishing but sportfishing boats were also available, as was barge fishing (the San Wan in the ’40s, the No-Name in the ’50s). That changed in 1961 when independent fishermen were able to convince the city to let them use the Navy Pier (built during the war year of 1942 and transferred to the city in 1959), which sat nearby in the protected harbor.

The loss of the commercial fisheries seemed potentially devastating until the intervention of oil into Santa Barbara’s economy and the extensive use that oil companies and allied business made of the wharf. Oil soon dominated the wharf’s activities (which created considerable unhappiness with local anglers and tourists). Then, on January 28, 1969, the environmental consciousness of local residents, Californians, and much of the nation was engaged by an oil spill that occurred in the nearby Santa Barbara Channel. Protests soon began (led in part by GOO—Get Oil Out) against the oil industry. Many began to question the role of Stearns Wharf and convinced the city fathers that perhaps a new vision of the wharf was needed. The city decided the wharf should be used primarily for recreational purposes and proposed an early termination of Castagnola’s lease.

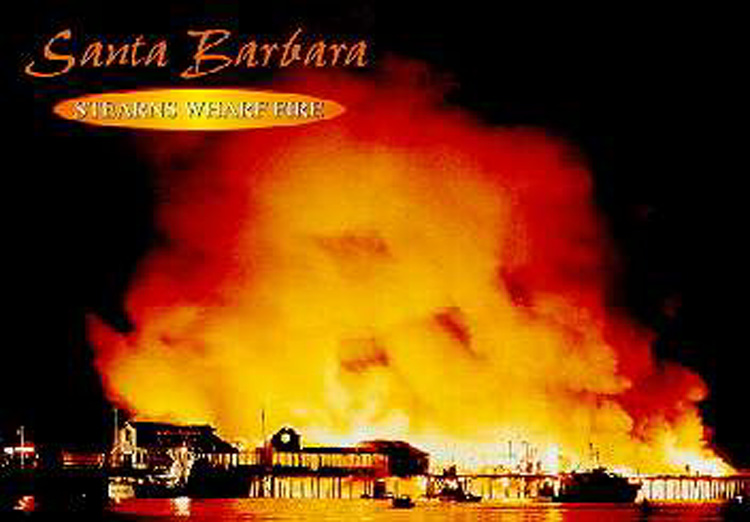

Six months before the lease was up, on April 14, 1973, an early morning fire destroyed George Castagnola’s Harbor Restaurant and much of the wharf. The city now took over the wharf and a long process began to determine the best use of the wharf and how it would be financed. The Coastal Commission rejected initial plans by the city but finally, with the help of the Coastal Conservancy; a plan agreeable to all was proposed and approved. Restoration began in 1979 and the wharf was re-opened in 1981.

As chronicled, there has often been damage to the pier, either from winter storms or from fires. One of the worst fires occurred on November 18, 1998 (less than a year after damage from an El Niño storm). Roughly 47,000 square feet of the pier, a strip about 140 yards long, was destroyed at the end of the pier. This area, of course, was the main area used by anglers. The $11 million blaze destroyed two restaurants, Moby Dick’s and the Santa Barbara Shellfish Company, and also destroyed the small bait shop which had been run by one of my web site’s most interesting reporters, Mike Katz of Mike’s Bait and Tackle. The section that had been destroyed was not reopened until late in 1999. Unfortunately Mike’s Bait and Tackle did not reopen. No longer could people check out the picture of the locally-caught 2,500-pound, 15-foot-long great white shark that graced the wall, or pick up the “feel good” rock from his counter, and I hated to see Mike leave. However, the good news is that the shop that replaced Mike’s, Stearns Wharf Bait and Tackle, is also an excellent shop and Frank Drew its owner does a similar excellent job!

________________

Stearns Wharf was not the only pier to grace the city’s curving shoreline during the early years of the Twentieth Century. Throughout California every beach side tourist area, and major seaside hotel, seemed to need a pleasure pier. The same was true locally. Santa Barbara’s “pleasure pier” was a 425-foot-long pier that was located next to the municipal bathhouse “Los Banos del Mar” at the foot of Castillo Street. The Edison Company, the company that operated Santa Barbara’s streetcar system, built the pier. Although primarily built as a support for the suction line that brought seawater to the power plant, it soon became a favorite of both swimmers and fishermen. It was built in 1895 (some sources say 1901) and used until 1929 when shifting sands from the harbor’s construction filled in the area around the pier.

None of Santa Barbara’s early piers and wharves remain with the exception of the venerable and iconic Stearns Wharf, a city treasure that is, in many ways, as important to Santa Barbara today as it was nearly a century and a half ago when birthed.

Stearns Wharf Facts

Hours: Open 24 hours a day.

Facilities: Lights, some benches, restrooms, an excellent bait and tackle shop (Stearns Wharf Bait and Tackle), restaurants and snack bars are all located on the wharf. Wharf parking is available at a cost of $ 2 an hour with some validation possible. There is some free 90-minute parking on State Street and there is also a city parking lot that costs $1 an hour.

Handicapped Facilities: Handicapped parking and restrooms on the pier. The surface is wood planking and although there are no railings, large pilings (to sit on) have been placed near the edge of most fishing areas. These would restrict handicapped anglers in some areas. There are some sections that have only a short, 6-inch wood curbing and these probably could be used.

Location: 34.40967136517077 N. Latitude, 119.68548774719238 W. Longitude

How To Get There: From Highway 101 take Castillo St. or State St. west to the beach and follow signs to the pier. State Street ends at the wharf where you are greeted by a water fountain featuring three gracefully arching dolphins. Right behind it is the toll station. Be warned that midday on a summer weekend may see every parking space on the wharf taken.

Management: City of Santa Barbara.

Awesome write up! Thanks. We just caught a 36 inch halibut off the pier, 6/25/19. Email me for pics

I used to fish Stearns Wharf all the time when I was a kid back in the late 80s / early 90s. I remember it was usually always really good for mackerel, with bonito and barracuda showing up usually in Sept. and Oct. There were also times when truly monster size halibut would show up and hang around the pier for weeks at a time. Other than that the fishing there for other species wasn’t all that great, and the surf area was pretty lifeless, no doubt due to the little 6 inch waves, just an occasional thornback and a corbina might cruise by every once in a while.

[…] Fish available at the pier are the normal southern California species with halibut, mackerel, jacksmelt, white croaker (ronkie), sand bass, kelp bass (calico bass), scorpionfish (sculpin), various perch, bat rays, and shovelnose guitarfish (sand sharks) dominating the catch. via […]