<*}}}}}}}}}>< — Because of the pier’s location, extending south from the shoreline’s east-west orientation, it’s possible to get up early and watch the sun rise over the ocean on one side of the pier. Later that night you can watch the sun set over the ocean on the other side of the pier. Neat, right?

Special Recommendation. One of the favorite tourist attractions on the pier are the Pelecanus occidentalis, the all too numerous brown pelicans that someone once said looked like a cross between a dinosaur and a ballet dancer. They sit there on the pier; waddle around, and trick you into thinking they are docile albeit dorky little playthings just waiting for a “Kodak Moment.” Don’t be fooled! They can also be aggressive, in fact overly aggressive. That fact was brought back to me on a visit in June of ‘98. Whenever I would catch a fish the big birds would hurry over hoping for a handout. Unfortunately for them I was returning most of the fish to the water. However, when I caught a large 17” mackerel I had to wrestle and actually push away several birds as I attempted to unhook the squirming fish. I’m not sure what they thought they would do with the mackerel since it was too big for them (I think)—it wouldn’t even fit in my cooler. Be careful not to leave bait out on the pier, either the pelicans or equally aggressive sea gulls will pull a disappearing act with your bait. Pelicans, by the way, have made the news since I first wrote the above words. The following article describes their plight and what some activists would like to do to pier fishing at the wharf. Help solve the problem by properly disposing of lines and hooks. And, don’t feed the birds

Brown pelicans in peril — Activists would like to see ban on wharf fishing

As more and more California brown pelicans become entangled in hooks and line at the waterfront, some activists say fishing on Stearns Wharf should be banned.

Volunteers for the Santa Barbara Wildlife Care Network, a nonprofit group, say they have been called to the harbor twice a week this summer to rescue pelicans wound up in fishing lines, with hooks lodged in their pouches, legs and wings. California brown pelicans have been on the federal endangered species list since 1970.

On Thursday, one of the birds, an adult female, died a day after she was rescued. She had been found at the Sea Landing jetty, mangled by four different fishing lines and hooks. One of her legs had been deeply cut by a line and the wound was infected and swollen, volunteers said. It was the 20th pelican the network had disentangled from fishing gear this year.

“Fishing is just doing so much damage to the birds,” said June Taylor, a Goleta resident who heads 21 volunteers in the network’s seabird program. “This last year, it’s been really bad. I feel like fishing off the pier should be disallowed. All of my volunteers feel this way.” Often, Ms. Taylor said, the pelicans will swoop down to grab the fishing bait in mid-air, hook and all, as the line is being cast into the water. “They’re attracted to the piers,” she said. “A lot of people are just so careless.” Hundreds of people fish off Stearns Wharf every week, catching mackerel, smelt, perch, barracuda, halibut and calico bass.

In an effort to protect pelicans, harbor officials have installed barrels on the wharf for the disposal of used hooks and line. They perform regular “sweeps” to remove dangling fishing lines—three times per week on the wharf and once a week or every two weeks below it, at water level. Next month, the city plans to erect signs in English and Spanish urging the public to recycle their hooks and line, said Mick Kronman, the harbor operations manager. Mr. Kronman noted that $250,000 of the money to rebuild the end of the wharf after the recent fire came from the Fish and Game Wildlife Conservation Board, with the stipulation that the wharf be used only for sportfishing and other recreational activities having to do with wildlife. “I think closing down the wharf might be a bit extreme,” Mr. Kronman said. “A more prudent course might be to pursue education.”

Fishing off Stearns Wharf Thursday, Raul Diaz said a ban would result in the loss of a relaxing and enjoyable pastime for many people, but he understood why some would want to bar fishing. “A lot of people cut their lines and leave it here on the pier or throw it in the water,” he said. As he spoke he pointed to a pelican hobbling around the pier. He said the bird only had one leg and most likely had gotten tangled in some fishing line. At the very least, he said, something should be done to monitor anglers to make sure they clean up after themselves.

Last week, the state Department of Fish and Game and the city of Santa Cruz imposed a temporary ban on fishing along two-thirds of the Santa Cruz pier to protect pelicans. Large schools of anchovies have attracted flocks of the birds there; more than 100 pelicans have become entangled in fishing line, state officials said. Twenty of those birds have died or been euthanized as a result of their injuries.

Santa Cruz and Fish and Game officials are patrolling the wharf daily, telling anglers to cast away from pelican feeding areas and how to release a hooked bird. Animal rescue workers are asking for a total fishing ban at the pier at least through next week, when the anchovy run is expected to be over.

On the Santa Barbara waterfront, the Wildlife Care Network continues to respond to emergency calls to save pelicans. Thursday, a volunteer was called to the Mission Creek bridge at the waterfront to capture a pelican less than a year old that was trailing a fishing line about 10 feet long. The line was wound around one wing, but not tightly enough to prevent the bird from flying. Seemingly aware of the volunteer with the big blue net perched on the banks, the pelican stayed out of reach and finally flew away.

In addition to pelicans, volunteers say they find grebes, cormorants and many seagulls wrapped up in fishing gear at the harbor. In recent months, several pelicans on the South Coast also have been injured by vandals. Diane Cannon, president of the wildlife network, praised the city for what it has done so far. “The city has been very helpful in working with us to put up signs,” she said. “They’ve been very supportive. It should make a real difference. Not having any fishing would make the biggest difference, but it’s not a realistic option.”

—Melinda Burns, Santa Barbara News-Press, September 7, 2001

History Note. The name Santa Barbara was applied to the offshore channel by Vizcaino on December 4, 1602, the day of the Roman maiden who was beheaded by her father because she became a Christian. Later the name was applied to the presidio, then to the mission, and finally to the city and county.

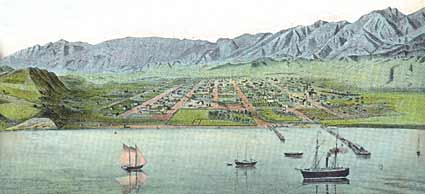

As is true at most coastal towns, the growth in the mid-1800s was accompanied by a certain amount of peril. The “schooners, the brigantines, the sloops-of-war, the square-rigged clipper ships,” and later the side-wheelers, were forced to anchor outside the kelp and unload their passengers and cargo by way of small boats—lighters—through the surf. As recorded, during “southeasters, every ship rode the swells beyond the kelp with slip-chains on her cables, ready if there came a blow, to fly at a moment’s warning and ride out the storm in the lee of Santa Rosa Island.” A wharf/pier was needed.

The first pier built in Santa Barbara was one that was built by the “La Compañia del Muelle de Santa Barbara”—the Santa Barbara Wharf Company. The company was composed of a polyglot group of local entrepreneurs— Samuel Brinkerhoff, New York physician; J.F. Maguire, exiled Irish patriot; “Dr.” P.B. Shaw, English gentleman, Luis Burton, Tennessee fur-trapper and Rocky Mountain pioneer; Isaac J. Sparks, Yankee trapper and seaman, and Martin M. Kimberly, sea captain. They received permission to build a wharf from the city council on September 18, 1865

_______________

Before the coming of the railroads in comparatively recent times, the sea furnished the most comfortable and convenient roadway to Santa Barbara’s door. The eyes of those whose memory runs back to sixty years light at the mention of the “Orizaba,” the “Pacific,” and other passenger steamers which touched regularly at the port…

In the ‘60s and ‘70s the ships carried much freight, and the stay in port was usually for several hours. When one steamed in on a Sunday afternoon, most of the population of Santa Barbara-able to walk turned out to welcome her. There was a line of open carriages in waiting. And in these vehicles passengers were taken for drives about the town. James L. Barker, a pioneer who died recently while on a world tour, spoke of those days to me as follows: “The Orizaba and the Senator were regularly on this run. They left San Francisco on alternate Saturdays and arrived here on Sunday afternoon between four and five o’clock. ‘Steamer day’ was our gala day.”

“The passengers were brought ashore in a whaleboat to the small wharf at the foot of Chapala Street. When the water was very rough, it was impossible to bring the boat alongside without danger, and so a barrel with half of the top cut away and a seat built in was used. One passenger at a time sat in the barrel and was hoisted to the wharf by tackle.”

—History of Santa Barbara County

Their pier was built at the foot of Chapala Street and opened in October of 1868. Unfortunately, the pier reached out only to the kelp line (500 feet) and was too short for deep-draft, ocean going vessels.

That last fact was important for local lumberman John Peck Stearns, a one-legged Vermonter who had hoped for a longer wharf. Since lumber schooners couldn’t use the Chapala Street Wharf, they would simply dump his incoming shipments of lumber overboard into the water and count on the tides to wash them ashore. That usually meant that at least some of the lumber would be damaged. Stearns soon offered to buy an interest in the wharf company and extend the Chapala Wharf but his offer was rejected.

In 1871 Stearns decided to build his own wharf, a longer wharf that would reach out into the deeper waters needed for safe anchorage. He then gained the backing of W.W. Hollister, Albert Dibblee, and Thomas B. Dibblee (the local money men/movers and shakers). A franchise to build a wharf at the foot of State Street was sought and, against the bitter opposition of the Chapala Street Wharf syndicate, it was granted to Stearns in July of 1871. Stearns had borrowed $41,000 from Hollister (with whom he had helped establish Santa Barbara College in 1869) and he soon ordered the lumber and pilings he would need for his wharf. Next, he hired the firm of Salisbury and Frazier, who had recently completed the Port Hueneme and San Buenaventura wharves, to build his wharf.

Just over a year later, the 1,500-foot-long wharf that reached water 21 feet deep at low tide was completed. Freighters and schooners, previously forced to float cargoes ashore, piggyback them on the backs of strong sailors, or bring them through the surf by surfboats (called lighters), could now load or unload directly at the pier. On September 16, 1872, the freighter Annie Steffer became the first vessel to visit the wharf. Passenger steamers, including the side-wheeler Orizaba, followed by the Senator, the Mohongo, the Kalorama, the Queen of the Pacific and many others, soon made Santa Barbara a popular port of call.

Stearns Wharf immediately became the center of beachfront commercial activity, much to the chagrin of the Chapella Wharf owners. When Stearns announced plans in the spring of 1873 to extend his wharf by 500 feet, the Chapella Wharf group raised money to lengthen their wharf by 1,000 feet. However, Stearns had the Salisbury & Frazier pile driver, the only one that was available, and they couldn’t extend their wharf. By July of 1873, Stearns had extended his wharf out to 2,200 feet and the new 24-foot depth at the end of the wharf allowed the large mail steamers to tie up to the wharf. Stearns’ Wharf became, for a period of time, the largest pier on the Pacific Coast, outside of San Francisco Bay. As such, it became the city’s “front door,” the economic center for Santa Barbara, and the most important wharf along this stretch of coast.

Awesome write up! Thanks. We just caught a 36 inch halibut off the pier, 6/25/19. Email me for pics

I used to fish Stearns Wharf all the time when I was a kid back in the late 80s / early 90s. I remember it was usually always really good for mackerel, with bonito and barracuda showing up usually in Sept. and Oct. There were also times when truly monster size halibut would show up and hang around the pier for weeks at a time. Other than that the fishing there for other species wasn’t all that great, and the surf area was pretty lifeless, no doubt due to the little 6 inch waves, just an occasional thornback and a corbina might cruise by every once in a while.

[…] Fish available at the pier are the normal southern California species with halibut, mackerel, jacksmelt, white croaker (ronkie), sand bass, kelp bass (calico bass), scorpionfish (sculpin), various perch, bat rays, and shovelnose guitarfish (sand sharks) dominating the catch. via […]