Hakes: Family Merlucciidae

Species: Merluccius productus (Ayres, 1855); from the Latin words merluccius (an ancient name meaning sea pike) and procuctus (drawn out).

Alternate Names: Cod, hake, silver hake, Pacific whiting, haddock, whitefish, popeye and oatmeal fish. Early-day names included mellusa and meluzette. In Mexico called merluza norteña.

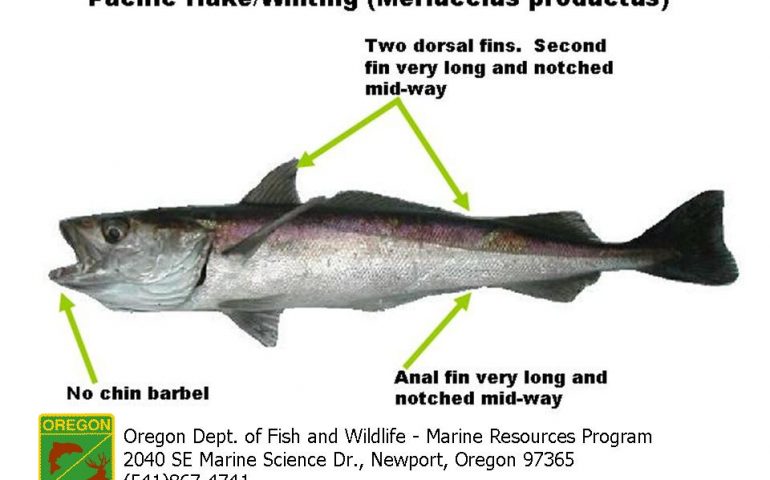

Identification: Very similar to cod but the second dorsal fin and anal fin are deeply notched (not separated into two fins) and the pectoral fin reaches past the end of the first dorsal. They have a mouth full of sharp teeth. Their coloring is metallic; blackish or iron gray above, shading into silver; black speckles on the back; the lining of the mouth is black. Considered a “slim fish with large eyes.”

Size: To 3 feet and around 10 pounds; most caught from piers are 18-24 inches long.

Range: From Bahia Magdalena, southern Baja California, to Attu Island, Aleutian Islands, Bering Sea (rare), Gulf of Alaska and Asia.

Habitat: A bentho-pelagic species commonly found from 160 to 1,500 feet deep but recorded from the surface down to a depth of 4,593 feet deep. Typically found over sand or mud. The schools are highly migratory apparently undertaking both vertical and horizontal migrations, inshore and out, shallow water to deep, seasonally. They are also nocturnal feeders that rise from their deep-water habitat to the surface at night where they feed on plankton; by daybreak they are once again in deep water. They’re considered impotant forage food. Juvenile hake are prey for birds, demersal sharks (those living near the seafloor), and rockfish. As they grow they are a major prey for the larger flatfish, pinnipeds, pelagic sharks (that live in the upper part of the ocean), and sablefish. I have caught quite a few hake at the Newport Pier and most were caught either at night or in the early morning hours.

Piers: Hake are an uncommon catch occasionally seen at piers located close to deep water. Best bets: Balboa Pier, Newport Pier, Redondo Beach Pier, Port Hueneme Pier, Monterey Wharf No. 2 and Santa Cruz Wharf. An exception is the shallow-water Pacifica Pier that seems to see a few most years.

Piers: Hake are an uncommon catch occasionally seen at piers located close to deep water. Best bets: Balboa Pier, Newport Pier, Redondo Beach Pier, Port Hueneme Pier, Monterey Wharf No. 2 and Santa Cruz Wharf. An exception is the shallow-water Pacifica Pier that seems to see a few most years.

Shoreline: A deep-water fish rarely seen inshore.

Boats: Rarely a sought after species but frequently caught by rock cod fisherman from Monterey north and occasionally taken by salmon trollers in northern California.

Bait and Tackle: Hake will hit almost any bait, dead or alive, but squid works best according to my records. Hake are usually caught by anglers bottom fishing for other species. Medium tackle, a high/low leader, and hooks size 4 to 2 are best. Almost all of these are caught at night.

Food Value: Fairly good but only if cleaned and iced down immediately after capture! Failure to do this will result in deteriorated, soft-fleshed (yucky) meat (or more properly mush) with excess moisture more suited for local Tomcats or gardens than the dinner plate. The reason? See below.

Comments: Salmon trollers in northern California often catch hake; the fish are typically killed and tossed back into the sea. Rock cod anglers fishing the deep reefs out of Santa Cruz also catch many. In fact, back when you could use the three-hook gangions and a diamond jig, I had days when I was sometimes pulling in three or four hake at a time when fishing for the more preferred red rock cod—canary, vermilion, chilipepper, bocaccio, and greenspotted rockfish. And, I remember one trip out of Stagnaros Sportfishing in June of ’83 when the hake were huge, some approaching 8-10 pounds in weight. Hauling up 2-3-4 of the heavy fish at a time quickly tired out the arms. Usually when the hake showed up the skipper decided to move since the hake were considered nuisance fish. Scientists report that hake are the most numerous commercial species along the West Coast and live to about 23 years of age.

The reason hake are looked down upon by anglers is that they are a very “delicate” species that require careful handling (and they usually do not get it). They deteriorate rapidly after capture due to a tiny parasitic protozoan in their muscle. This nasty little critter, Kudoa paniformis, produces an enzyme that actually liquefies the muscle tissue. When the hake are alive they are apparently able to remove this enzyme quick enough to maintain their Olympian shape. However, after capture by mystified pier anglers, the hake die quickly. Not so for our little friends, the kudoa. They live on for a period of time, continue to produce this enzyme, and the flesh turns to mush. The parasite is in no way harmful to humans (even if eaten alive) but hake mush just isn’t considered a delicacy by very many pier anglers. After all, pier anglers are considered the Epicurean class among sport fishermen. However, if cleaned and cooked immediately after capture (rarely an option) they are considered fairly good eating.

Hake caught from the Stagnaro deep sea boats at Santa Cruz

Nevertheless, Hake have become an important commercial species. In fact, they are the largest commercial species on the coast. According to Agriculture and Agri-Food of Canada, “a surimi industry has been developed on the west coast of Vancouver Island for which Pacific whiting [hake] is the principal resource. The strict use of temperature controls in holds of fishing vessels, removal of fish from boats by pumps (which also pump the fish into the plant), use of an enzyme inhibitor created from potatoes, and insistence on quick and efficient processing have enabled Canadian companies to produce not only top-quality, inexpensive surimi, but also the best frozen whiting fillets and blocks available.” Surimi is the fish paste used in making crab-flavored seafood. So, next time you pick up that fake crab meat, you probably will be eating hake. However, the fish have been declared a species of concern since 1999 due to overfishing.

Apparently their less than good taste has been noted for some time— “John Suhl caught an 8-pound hake off the end of the [Santa Cruz] wharf. The fish, the first of its kind taken in some time, is not appreciated by humans, so it was cooked for dog food.” —Santa Cruz Sentinel, July 28, 1954