Damselfishes: Family Pomacentridae

Species: Hypsypops rubicundus (Girard, 1854); from the Greek word hypsypops (high area below the eye) and the Latin word rubicunda (red).

Alternate Names: Golden perch, ocean sunfish and ocean goldfish. In Mexico called jaqueta garibaldi. As for the name garibaldi, it apparently was a name bestowed upon the fish by California’s Italian commercial fishermen in the 1800s. Giuseppe Garibaldi was one of the main leaders in the unification movement to create an Italian nation and his followers were known as the “Redshirts” for the bright red shirts they wore. He was considered a hero to Italians throughout the world and apparently the fish, at least to some, were reminiscent of those red shirts.

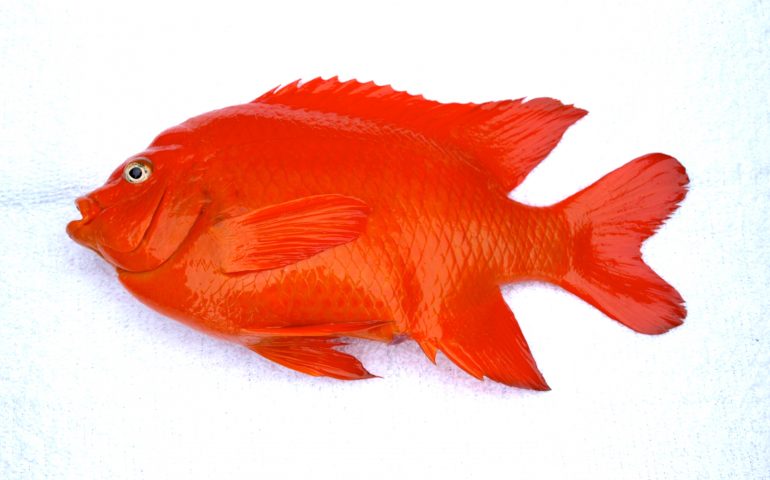

Identification: Garibaldi are easily distinguished by the brilliant golden-orange coloring on the whole body and are considered by many the prettiest fish in our coastal waters. They are perch-shaped but very deep-bodied with large fins. The young (up to about 6 inches in length) are reddish orange with bright blue spots.

Juvenile Garibaldi with blue spots

Size: To 14 inches (some books say 15 inches) but most pier-caught fish are under a foot in length.

Range: Southwest corner of the Gulf of California, Islas Revillagigedos and Tres Marias, and the Pacific Coast from southern Baja California, to Monterey Bay in central California. Common from Bahia Magdalena, southern Baja California, to southern California. Uncommon north of Santa Barbara and rare north of Point Conception. Extremely common at Catalina Island, which is sometimes referred to as “Garibaldi Central” by scientists and divers.

Habitat: Generally found in shallow-water, rocky-shore areas although they have been encountered down to a depth of 128 feet. Fitch and Lavenberg, Tidepool and Nearshore Fishes of California, report that “A wide variety of food items has been found in garibaldi stomachs, including sponges, sea anemones, bryozoans, algae, worms, crustaceans, clams and mussels, snail eggs, and their own eggs.” No wonder it is sometimes hard to keep them off a hook even though they’re illegal to keep.

Piers: Often hooked at southern California piers located near kelp beds or rocky reefs. Best bets: Oceanside Harbor Pier, Dana Harbor Pier, Redondo Harbor Sportfishing Pier, and the three main piers on Catalina island—the Green Pleasure Pier and Cabrillo Mole at Avalon (where it’s hard not to hook them), and the Isthmus Pier at Two Harbors.

Shoreline: Occasionally hooked by rocky shore anglers in southern California.

Boats: An inshore species rarely taken from boats although some are hooked, and hopefully returned, by kayakers fishing in shallow water, rocky areas.

Bait and Tackle: None—illegal to take

Food Value: None since you can’t keep them.

Garibaldi from the Cabrillo Mole in Avalon

Although pretty to look at, they are pugnacious, strong, and not the friendliest fish. They are extremely territorial and will defend fairly large areas. This is especially true during the spring-summer spawning season when males will build a nest and defend it against intruders, both fellow male garibaldi and other species (including humans). Apparently the cute little missy garibaldi are an exception and allowed to invade those spaces and deposit their eggs.

It is illegal to keep these fish, but why? As related to me by a Fish and Game official, the campaign to make them illegal originated in Avalon. It seems that the glass bottom boats, a popular attraction at Avalon on Catalina Island, were worried that anglers (actually divers) were taking far too many of the beautifully colored fish and that it was bad for their business (since garibaldi are one of the most viewable fish from the boats).

According to records, in January 2, 1953 the California Department of Fish and Game presented proposals to “prohibit skin dive fishing along the waterfront of Avalon, Santa Catalina Island.” The proposal was based upon a similar proposal from the Santa Catalina Island Company. That proposal was met with opposition from spear fishermen so the proposed regulation was modified into a statewide prohibition on the recreational take of garibaldi. On January 30, 1953 the California Fish and Game Commission adopted the prohibition against the take or possession of garibaldi by angling or diving (Title 14, CCR, 28.05).

Thus the take of garibaldi by anglers in California has been illegal for over 60 years. However, a limited commercial take of garibaldi was permitted until 1995 when the legislature passed a bill (which Governor Wilson signed) placing a three-year ban on the commercial collection of garibaldi. Eventually the ban was made permanent.

The 1995 legislation also made the garibaldi the official “marine” or saltwater fish of California. Golden trout remain the “freshwater” fish.

Today, most anglers return the fish to the water if they’re mistakenly hooked. Nevertheless, some continue to be speared illegally. It seems colorful fish are required at the wedding dinner tables of some Pacific Islanders and garibaldi are a favorite. Once again long-time cultural tradition clashes with today’s rules.

As mentioned, the protection of garibaldi originated at Catalina where they have long been a favored fish (although called different names over the years): “many of the fishes described are of especial interest, as they are peculiar or indigenous to this region. With them is seen the brilliant orange-colored angel-fish, or golden perch, which sometimes takes a small hook. Its young are called electric fish by the amateur savants of the glass-bottom boat, as they are a vivid blue, almost iridescent, color, seeming to flash and sparkle like gems. When very young they are entirely blue, but gradually change to yellow as they grow older, until, in the adult stage, they are entirely yellow or a reddish-yellow.”—The Fishes of The Pacific Coast, Charles Frederick Holder, 1912

The Finny Bachelor by W. E. Cortissoz

I know a little garden, Beneath a green-gold sea

Where bright, bronze plants are growin’, And grow so gracefully.

Amidst their undulations, A flash of gold I spied;

And in and out the waving, Kelp it seemed to hide.

It was a little gold-fish, Who lived there all alone,

In this most lovely garden, In the Bay of Avalon.

Day after day I find him, Alone in his domains;

He darts, then lingers, to and fro, And in his garden reigns.

I see that he is happy, And that—his praise’ to One,

Who caused his life to happen, In the Bay of Avalon.

“Neath the music of the waters, In his garden of the sea,

Long may that garden denizen, Enjoy immunity.

Immunity from humans, And maws of ev’ry gauge;

I want my little goldfish, To pass away from age!

Catalina Islander, March 26, 1924

It’s interesting to learn that these fish are illegal to keep due to conservation efforts, highlighting the importance of preserving marine life for future generations.