Shark Attacks Diver Near Pier at La Jolla

La Jolla (AP)—An engineering aide at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Earl Murray, today reported that he was attacked by a shark as he was diving at 65-foot depth 600 yards off the end of Scripps Pier. Murray said that he was searching for a lost anchor when he noticed a 6-foot shark circling him about 10 feet over his head. “I stayed on the bottom as long as possible,” he said, “hoping to hide from the shark, but I had to come up because of shortage of air.” Murray was equipped with a fishing spear which he used to jab at the shark as he ascended. “I drew blood from the shark as he came within arm’s length of me,” Murray declared. He managed to elude the shark and swim to a boat 200 feet away. He was uninjured. This was the first reported shark attack in more than one and one-half years in this area. In December, 1955, a 6-foot shark bit off a diver’s swim fin near Scripps Pier. —Los Angeles Times, July 30, 1957

State Joins in Search for Shark

San Diego (UPI)—the State Fish and Game Department joined Scripps Institute of Oceanography Thursday in a search for the La Jolla Cove killer shark. Boats were scouring the area where Robert L. Pamperin, 33, was killed by a shark Sunday. Capt. Donald E. Glass, marine warden in charge of the hunt, said baited hooks would be planted from bird rock to the Scripps Pier in La Jolla. Scripps baited special hooks Wednesday with whale meat and dried cows blood to attract any man-eaters which might still be in the area. Nets 100 yards long were strung in the vicinity, but no catches were reported. However, Wheeler. J. North, a biologist at Scripps Institute, said he received reports of two shark sightings Wednesday. Je said two boys on paddle boards about one-half mile from the Sunday death site reported seeing a large shark in the water below tem and it was rumored a patrol boat ion the area sighted one of the man-eaters. Biologists claimed the shark which devoured Pamperin probably was a 20-foot tiger shark. They said if the man-eater still was around it would be accompanied by other sharks. Unusually warm currents off the Southern California coast were believed to be attracting the tropical sharks which normally frequented waters off Baja, California. —Long Beach Independent, June 19, 1959

<*}}}}}}}}}>< — Two marine life protective areas now blanket the pier. To the south of the pier is the Matlahuayl State Marine Reserve that prohibits the take of all living marine resources. Adjoining that reserve and extending north is the San Diego-Scripps State Marine Conservation Area. The pier itself sits in the San Diego-Scripps SMCA which prohibits the take of all living marine resources except for the recreational take of coastal pelagic species—northern anchovy, Pacific sardine, Pacific mackerel, jack mackerel—and market squid. In essence, these species are allowed for the kayak anglers in the area since anglers cannot fish from the pier.

<*}}}}}}}}}>< — One of my favorite places to visit when I am visiting San Diego is the Birch Aquarium (although known by most of us old timers as the Scripps Aquarium). It’s the public outreach center for Scripps Institution of Oceanography and sits on a hillside with great views of the Pacific Ocean.

There are tanks of fish from many areas of the world but for me the tanks showing the local Pacific species are most interesting. “Know thy fish” is a maxim I tell the “Pier Rats” and what better way than to see them up close and personal in their environment? Of note in the history of the aquarium seen below is the fact that for many years local anglers were allowed to fish from the pier.

A public aquarium has been a feature of the Scripps Institution since before it was an institution, because the members of William E. Ritter’s summer study sessions, which began in 1892, always had a few display tanks for interested visitors. When the Marine Biological Association of San Diego set out to establish Scripps Institution in 1903, they listed as one of their objectives: “to build and maintain a public aquarium and museum.

In 1905, in the “little green laboratory behind the bath house” in La Jolla Cove Park, a few shelves were set aside for a museum display, and a central counter held open containers of live specimens (some of which vanished with visitors). Five years later the public aquarium was located on the ground floor of the institution’s first permanent building, the George H. Scripps Laboratory.

In 1915 a separate public aquarium was built, a wooden building 24 feet by 48 feet, just north of Scripps Laboratory… The following year the museum, previously located on the second floor of Scripps Laboratory, was moved into the ground floor of the newly completed library building… The curator of both aquarium and museum was Percy S. Barnhart, who had joined Scripps in 1914 from the Venice (California) aquarium operated by the University of Southern California.

Barnhart’s usual technique of acquiring exhibits for the aquarium was by fishing from the pier. In the 1930s some specimens were gathered from the Scripps and the E. W. Scripps, and, during World War II when the institution had no ship, Barnhart kept a trap set off the end of the pier for gathering new material.

As early as 1925 the curator was complaining, in his annual reports, that the aquarium tanks were gradually disintegrating, and that “bad water, cracked glasses and broken tanks [were] a constant source of worry and aggravation.” … Barnhart also dreamed of the ideal aquarium-museum. His vision was a building in which brightly lighted display tanks would form a periphery around a central museum room. That vision became the design theme of the new aquarium-museum. Barnhart retired in 1946, while his dream was still only in the planning stage, and Sam Hinton, who had joined the staff a few months earlier, became the next curator.

The new aquarium-museum building was completed and occupied in October 1950 [and named for T. Wayland Vaughan, the second director of the institution]. As the Aquarium-Museum has never been supported by research funds, attempts to make it self-supporting have periodically led to the suggestion of charging admission. Hinton wrote eloquently against the idea in 1954: Many La Jollans have a proud sense of proprietorship in the Scripps Institution, and enjoy bringing their visitors to see “their” aquarium and museum…

Many local youngsters start nearly every summer day with a routine tour of inspection of the aquarium; these boys and girls are always delighted with new specimens and new exhibits, and frequently conduct their parents on guided tours on weekends. Lots of groups of families organize beach picnics and parties with the Aquarium as a meeting place; a tour of the place before and after is usually the order of things. These examples of the public attitude are individually small, but they add up to the fact that we enjoy a position of high prestige, and are considered by the community as a whole as part of the civic family. It would be most regrettable if this standing were to be lowered, as I feel it would be if each person were required to pay for admittance. It is surprising to realize that a considerable amount of bitterness still exists because of our having closed the pier to public fishing, nearly fourteen years ago… The issue of charging admission was shelved at that time…

The score of illuminated display tanks, in several sizes up to 2,000 gallons, have presented a colorful array of inhabitants through the years. Recently the displays have been composed of natural habitat groupings, chiefly of the San Diego area and of the Gulf of California region, where a much more tropical fauna dwells. Much admired by visitors are the orange garibaldis, dubbed the “La Jolla goldfish,” and their blue-spotted young. An especially popular aquarium personage for some years was Harvey, a 100-pound grouper, who majestically circled a large corner tank from 1956 until his death in 1973. Morays, as they stretch open their mouths to display an array of needle-sharp teeth, draw awed gasps from viewers. At times sea turtles have swum the rounds of the larger tanks, and at least briefly one tank displayed highly venomous sea snakes, carried home from a tropical expedition…

The seawater line was renovated in 1964, to increase the capacity and improve the filtration system. Seawater for Scripps needs, including the aquarium, is drawn in from the far end of the pier, by means of two vacuum-assisted pumps that lift the water to a wooden trough that slopes to the landward end of the pier. It passes through a sand-bed filter and is then stored in two tanks near the aquarium building. From one the water flows by gravity through the Aquarium-Museum, the Experimental Aquarium, the Physiological Research Laboratory, Ritter Hall, and Scripps Building. From the other storage tank seawater is pumped up to the Hydraulics Laboratory and the Southwest Fisheries Center… As a convenience to the public, a seawater tap was installed at the landward end of the pier in 1972. Home aquarists stop there regularly to fill jerry cans, bottles, and buckets…

In cooperation with area schools, Wilkie set up a career-training program for high school students interested in aquarium or marine biology careers… The very popular Junior Oceanographers Corps (JOC), for students from fourth to twelfth grade, is also under the auspices of the Aquarium-Museum. Roger Revelle and Sam Hinton began it, originally as a means of allowing enthusiastic young fishermen to fish from the pier and as a source of specimens for the aquarium tanks. Hinton organized JOC in March 1959, as a monthly lecture program; members had the privilege of fishing from the pier on weekends, but with the requirement that the catch must be offered first to the aquarium. Finding adult supervisors proved difficult, and over the years boats and equipment on the pier were occasionally damaged, so in 1964 all pier fishing was again forbidden…

The central museum area was given a major face-lifting in 1968… In the spring of 1975 the Aquarium-Museum opened its outdoor tide pool exhibit… The display features a unique tidal cycle: a three-foot tide that rises and falls every four hours. Periodically waves wash through the pool to simulate natural conditions… Local marine denizens from nearshore areas inhabit this display, in a hide-and-seek fashion that is typical of tide pools of the San Diego area…

Aquarium tenders learn to avoid the poisonous stonefish and lionfish, and the threatening gape of the morays (only Ben Cox regularly petted those, during his many years of feeding the fishes). They have found the octopus to be the most troublesome aquarium inhabitant, as it is inclined to wander. Several times octopi have been found on the floor by startled janitors or staff. Late one night a restless — or hungry — octopus crawled from his own tank into his neighbors’, inadvertently dragging along his probably life-saving refrigeration unit. The neighbors were crabs, which the octopus was eating when discovered. A hastily called aquarium crew wrestled for twenty minutes with the 35-pound octopus, prying loose the 2,000 suckers of his eight arms. As they lifted him out of the tank, he reached back to snatch one last crab. —Elizabeth Noble Shor, Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Probing the Oceans, 1936-1976, 1978

By 1985 a new aquarium was needed and the Stephen and Mary Birch Foundation began to raise funds for its construction. In 1992 a new, $14 million Birch Aquarium opened its doors on land donated by UC Sad Diego. The new aquarium had a number of new exhibits but new ones continue to be added. Recent exhibits have included the following—the Hall of Fishes, Shark Reef, Elasmo Beach, Coral Reef, There’s Something About Seahorses, Tide-Pool Plaza, Boundless Energy and a 70,000-gallon live kelp forest tank.

History:

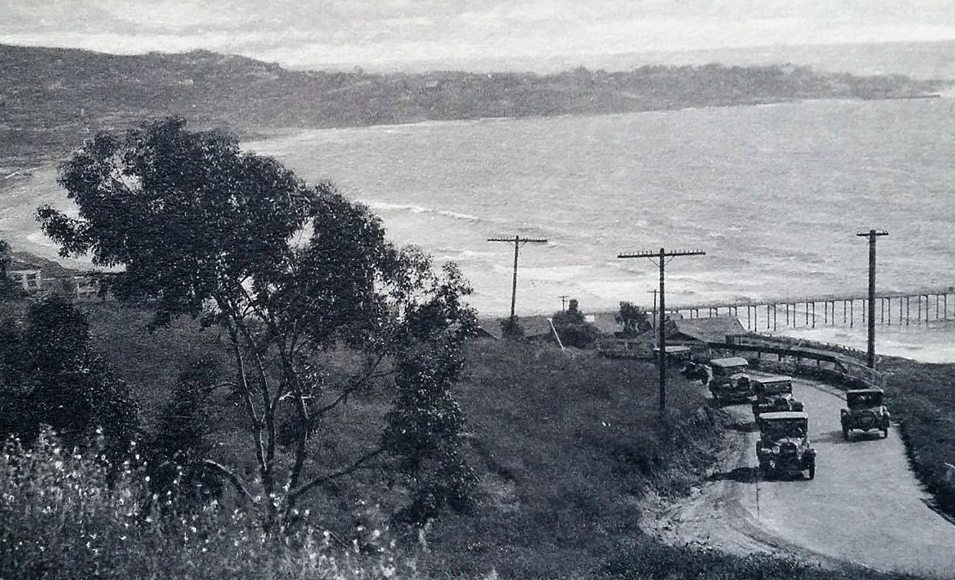

Old Scripps Pier Will Soon Be Headed for Davey Jones’ Locker

as i recall sam hinton fid keep one alive long enough to put on display in the aquarium.i also remember sitting on cliffnorth of scripps watching severalmedium sized shark swimming around dike rock a reef of the pier a quarter mile or so. this was at the same time that the sharks were being caught off the pier.

Would loved to have seen that.

This article refers to sharks as “dangerous”, “killer”, “man-eating”, “man-eater”. With the incredible amount of information available today, including research that has been conducted by SIO, it is confounding that you would publish such sensationalized, inane, highly inaccurate misinformation regarding sharks. This only serves to reinforce the age old negative stereotype of sharks which has placed a cloud of fear over the general public and contributed to the extermination of 90% of the global shark population. Please, do your research and better inform yourself on shark behavior, shark-human interaction, and what you can do to HELP, not harm, the protection of sharks who are critical to the health of our marine ecosystems. Yes, the health that supports stocks and populations you depend on for recreational fishing. There are far more recent records of human-shark interactions. Pacific Coast Shark News keeps up-to-date records of reports. This was otherwise would have been an engaging and informative article. Note: I have a marine biology degree from SIO and also worked for CA Fish and Wildlife collecting data regarding marine recreational fishing around San Diego county.

Did you even read the article? What you reference are newspaper headlines for each of the historical stories mentioned. If I am going to report the newspaper stories of the day I have to use their language, I can’t pretend those headlines didn’t exist or make up new headlines.

I know many of the top marine biologists in the state including some often noted as “shark experts,” I have served on several statewide fishery committees (including the MLPA), and have LONG advocated the ethical treatment of all fish, not just sharks (see the Pier Rats Code).

I share many of your views on sharks but am not going to change a quote simply to avoid “words.” If you read the entire article you would see that nowhere do I attack great white sharks in the manner you suggest. I have written literally hundreds of articles and in none have I ever attacked great whites in a derogatory manner and in fact I have often praised those who go out of their way to protect these and other sharks.

You need to do your homework better before attacking someone in such a manner.

Ken Jones